Billy Connolly once quipped “There are two seasons in Scotland. June and winter.”

That might have been teetering on the harsh side, but it has its roots in reality. Apart from memories of British summers being longer and hotter than they are now (the same memory we all seem to share), whenever I think of Scotland in sunshine, it tends to be during one of the spring months.

One of our first trips together involved gazing at a fiery sunset, one which has rarely been bettered, on a balmy May evening in Oban. The year we swapped Britain for somewhere with friendly year-round weather we chugged our way through the Kyles of Bute on my brother-in-law’s wooden fishing boat to anchor in a remote bay in the north of Bute where we enjoyed a picnic on the beach on a warm April afternoon. It was an exceptional day, a day filled with fun and nonsense – an out of control Zodiac and also our stock of beer and wine being washed away from the makeshift refrigerator (i.e. a rock pool).

It’s been a long, long time since I left Scotland, but as well as memorable experiences there’s something else which wraps itself around my shoulders whenever we spend any time there. It’s a comfort blanket; a sense of feeling relaxed, being amongst kin and of escaping to a world scripted by Bill Forsyth with hints of Irvine Welsh thrown in to add that essential realistic grit.

I haven’t been in Scotland during spring for many years, yet our last visit felt springlike. If not always in relation to the weather, at least in the sense of a refreshing blowing away off the cobwebs – a cerebral clean-out which reminded me there are still plenty of people who don’t confuse spouting trashy news headlines with having a conversation.

Argyll & Bute

On the Cal-Mac ferry, which links my birthplace Rothesay with the mainland, we bumped into a couple who played a big part in my transition into adulthood. Donny and Margaret had owned the bar where my friends and I spent nearly every happy night for a number of years drinking too much, putting the world to rights and playing pool, darts and chess. The latter was against a fisherman who was perpetually blind drunk but rarely lost a game. I hadn’t really spoken to Donny in over 30 years, yet the past melted away and so did time as we crossed the choppy, petrol coloured Clyde waters and ate bacon rolls in Wemyss Bay railway station; a remarkable architectural work of Victorian art (not appreciated at all during the numerous times I had to pass through it to get to ‘civilisation’). Donny’s smiling face and intelligent conversation swirling from one topic to another, bonded by down to earth common sense, had me leaving the train in Paisley with a renewed spring in my step.

Dumfries & Galloway

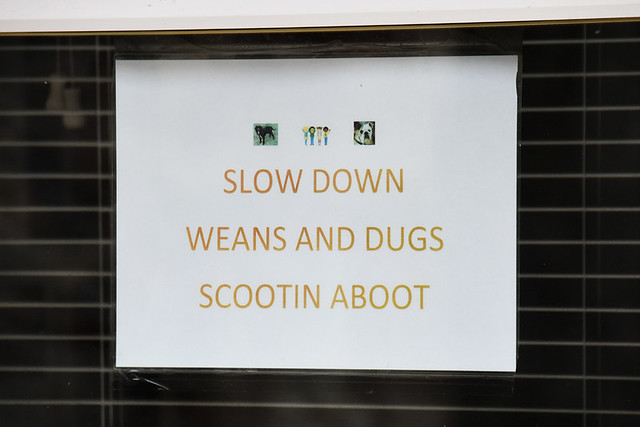

In Scotland’s highest village Wanlockhead, a place which made a ravine of an impact, the trio of staff (locals) who shepherded us from one part of the village to another did so with an easy friendliness, wit and enthusiasm which drew us into the world of the village, opening up revealing portals to give us glimpses of a far harsher lead-mining community past. It was pure Local Hero territory, one window displayed the notice – “Slow down, weans and dugs scooting aboot.”

Stirling

Drookit to the point of having sodden underwear after a wet, windy and glorious walk, we found a warm sanctuary in the solitary Drovers Inn at Inverarnan near the head of Loch Lomond. Bar staff, looking like uber-cool hipster Highlanders in their black tee-shirts and kilts, waved away concerns about us ‘soiling’ the aged seats and even checked out the time the bus would arrive at the stop opposite so we could maximise our beer-sipping time. This was an inn I could have happily settled into for a long session of supping amber ales and listening to the chatter from haggis and tattie-munching punters at the next table. The bus turned up far too quickly and, along with a brace of spliff-smoking German lads wearing fake kilts, we left the Drovers to enjoy the scenery on the way back to our hotel from the dry comfort of the bus… where we did leave damp patches on seats.

Highlands

And then there was Skye – dramatically raw, indisputably bleak in parts, and completely captivating. Even the most eye-catching wrappings need additional ingredients to give them substance. In Skye’s case this was mostly provided by the people we encountered. The owners and staff at Hame on Skye, who really did make it feel like ‘hame’. The convivial ambience at Hame was also partly down to the people who passed through during our couple of nights there. These included wry Americans and sensible Scandinavians, and a softly-spoken whisky maker who popped in for a drink (not whisky) after work. He shared eye-widening insights from the world of uisge beatha (water of life), debated politics in an old fashioned way (i.e. listen to and consider other points of views) and gave us priceless tips on where to explore.

Perth & Kinross

As the chatty curator’s collie stopped me from handing over the entrance fee to Cultybraggan Camp near Comrie by continually forcing a chunk of wood into my hand for me to throw across the confined limits of the Nissen hut, it was impossible to imagine it had been a ‘black’ camp during the Second World War. This was one of only two prisoner of war camps in Britain designed to hold the most fanatical Nazis. Now it’s a museum, and a reminder of a dark and dangerous time when Europe was fragmented. A story concerning one inmate highlighted some of the best qualities of the British character. Heinrich Steinmeyer was a member of the Waffen SS who was captured in Normandy in 1944. Three times his life was saved by Scottish soldiers before he ended up at Cultybraggan Camp. When the war ended he stayed in Scotland until 1970 when he returned to Germany to care for his elderly mother.

When Steinmeyer died in 2014 he bequeathed all his savings, nearly £400,000, to the residents of Comrie as a thank you for the kindness he had been shown by locals during his imprisonment. In 2009 he made this comment about his captors.

“They were tough, but always fair. I didn’t expect to find this attitude. I was not just the enemy, but a Nazi as well. Such friendliness was a surprise. But it is in the British nature.”

It was qualities such as those Steinmeyer had been referring to I felt we’d witnessed time and time again during our trip around Scotland.

You could argue that I’m possibly viewing things through romanticised tartan sunglasses. But our experiences are our experiences, and the ones we had in Scotland in September 2018 left me with renewed hope regarding my fellow humans.

Be the first to comment